Can the Central Bank of Bolivia control inflation?

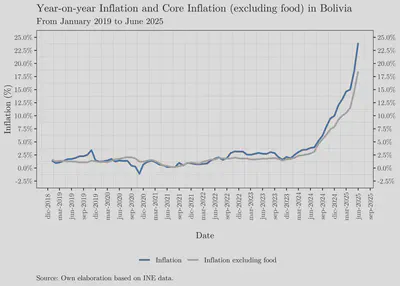

Since late 2023, inflation in Bolivia has shown a significant acceleration. In June 2025, the latest available data, the year-on-year variation of the consumer price index reached 23.96%. Compared to the previous month, the basic basket registered an increase of 5.21%. When annualizing this monthly rate, we obtain a projected inflation of approximately 83.94%:

$\textit{Annualized monthly inflation} = \left(1 + \frac{5.21}{100}\right)^{12} - 1 \approx 83.94\%$

This phenomenon is no longer limited to specific products nor can it be attributed solely to transitory factors such as road blockades, social conflicts, or climate events. Inflation has spread across virtually the entire consumption basket. As seen in the graph below, even when excluding the most volatile components —such as food— core inflation, which is usually more stable, has also increased considerably.

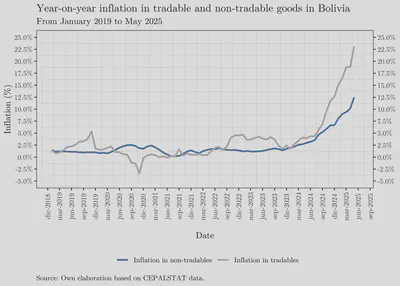

Another useful way to analyze inflation is to distinguish between tradable products —those that can be traded internationally— and non-tradables, meaning those whose price is mainly determined domestically. In the Bolivian context, where the parallel exchange rate is more than double the official one, the prices of tradable goods are usually the first to reflect this exchange rate distortion, as they are more directly exposed to import costs.

On the other hand, the prices of non-tradables —mainly linked to services and locally produced goods— tend to adjust more slowly. However, as shown in the graph below, this dynamic has begun to change.

The graph shows the year-on-year inflation trend for both tradable and non-tradable goods up to May 20251. As expected, from 2023 onwards, tradable goods began to register significant increases, reaching an almost 20% year-on-year variation in May 2025. However, the most revealing aspect is that inflation has also accelerated in non-tradable goods, reflecting a broader pass-through of price increases across the economy, including traditionally more stable sectors such as services.

Moreover, aside from a few subsidized products such as gasoline or gas, most goods have experienced significant price increases. This can be seen in the graph below.

Furthermore, although official and alternative data are not always directly comparable, tracking prices published by online supermarkets illustrates the magnitude of the problem. In just six months, products such as onions, peas, cabbage, and lettuce have doubled in price, recording increases of over 100%.

In this scenario, one must ask: can the Central Bank of Bolivia (BCB) control inflation?

Theories of Inflation

Inflation is a complex and persistent phenomenon, which has been addressed from various theoretical perspectives. Among the main ones are the monetarist theory, which attributes inflation to excessive growth of the money supply; the Phillips curve, which relates inflation and unemployment, with a central role for expectations; and more recently, the fiscal theory of the price level (FTPL), which emphasizes fiscal sustainability and the real value of public debt2.

In principle, the Central Bank —through its monetary policy— should be able to intervene on the key determinants of inflation. However, its effectiveness depends on the institutional and fiscal context in which it operates.

BCB’s Monetary Policy

Exchange Rate Policy and Inflation

The fundamental mandate of the Central Bank of Bolivia is the stability of the national currency’s purchasing power, as established in Article 2 of Law N° 1670:

Article 2. The objective of the BCB is to ensure the stability of the internal purchasing power of the national currency.

Although the law does not explicitly define what is meant by “price stability,” it is commonly interpreted as maintaining low and stable inflation3. To achieve this goal, the BCB uses monetary and exchange rate policies as its main instruments.

Regarding exchange rate policy, since the implementation of Supreme Decree 21060, the BCB recognized the relevance of the exchange rate as a transmission mechanism for prices. On one hand, given Bolivia’s heavy reliance on imported goods —including agricultural inputs and capital goods— any depreciation of the exchange rate has an immediate effect on domestic prices. On the other hand, the exchange rate also influences inflation expectations, affecting decisions related to consumption, investment, and price-setting.

For these reasons, since the 1990s the BCB has used the exchange rate as a nominal anchor. This is explained by Juan Antonio Morales, past president of the BCB, in chapter 7 of the book “Contemporary Monetary History of Bolivia” (BCB, 2005), referring to the exchange rate as the main tool for price stabilization:

Generally, small countries, as well as many medium-sized ones, base their monetary policy on the exchange rate […] The fixed but adjustable exchange rate, as in our country, serves as the nominal anchor.

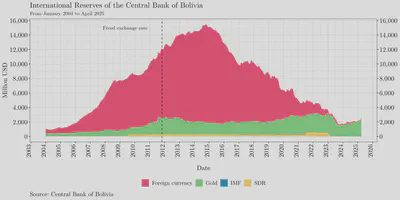

This regime allowed prices to remain relatively stable for over a decade, although in November 2011 it was fully pegged to the US dollar due to the abundance of foreign currency from gas exports.

However, since around March 2023, and due to the depletion of BCB’s international reserves, the system has become unsustainable. The existence of a parallel market with a rate double the official exchange rate has undermined the effectiveness of the exchange rate anchor.

As a result, the BCB has lost both the ability to effectively intervene in the foreign exchange market and the institutional credibility needed to anchor expectations. The breakdown of the exchange rate regime not only exacerbates observed inflation but also weakens the BCB’s ability to fulfill its price stability mandate under current conditions.

Fiscal Policy and Inflation

The main challenge to price stability in Bolivia is the sustained fiscal deficit. As argued in this previous entry, the BCB’s limited independence, together with the government’s inability to finance itself through conventional means —such as tax revenues or debt placed in markets— has led to a short-term solution: direct deficit financing through BCB loans to the National Treasury (TGN).

This practice is economically equivalent to monetary expansion. Issuing money without a corresponding increase in production raises the money supply in circulation, generating inflationary pressures. If there is also a loss of confidence in the national currency, this process intensifies and becomes more difficult to reverse4.

Can the BCB Control Inflation Under These Conditions?

Practically speaking, no. Suppose the BCB adopts a strictly anti-inflationary stance: it suspends loans to the TGN and implements a contractionary policy to absorb liquidity from the system by raising interest rates. This strategy could slow inflation in the short term, albeit at the risk of a severe economic contraction, as anticipated by both monetarist theory and the neo-Keynesian Phillips curve.

However, if the government continues running fiscal deficits without an alternative source of financing, political pressure on the BCB would resurface. Sooner or later, the monetary authority would be forced to resume assistance to the Treasury, thus restarting the inflationary cycle. This is precisely the argument made by Sargent and Wallace (1981): when there is fiscal dominance, monetary policy alone cannot control inflation.

Fiscal Dominance: Is There a Way Out?

Overcoming a regime of fiscal dominance is no easy task. There are no quick fixes or shortcuts, but there is a clear path: moving toward fiscal sustainability. This requires a firm correction of the public deficit. As proposed by the Populi Center for Studies, a well-designed fiscal consolidation program can help restore budgetary balance and reduce pressure on monetary policy.

At the same time, it is essential for the BCB to regain its institutional independence. Only then can it conduct a credible monetary and exchange rate policy genuinely aimed at price stability. This requires, first and foremost, an end to monetary financing of the fiscal deficit and a clear separation between the fiscal and monetary functions of the State.

As discussed in this complementary entry, neighboring countries have managed to break fiscal dominance by implementing credible fiscal rules and restoring central bank autonomy. In all cases, success required broad and sustained political consensus.

In this context, the BCB should reconsider its monetary policy framework. A viable option is the adoption of an explicit inflation targeting regime, successfully used by several central banks in Latin America5. This approach would involve setting a quantitative inflation target, communicating it transparently to the public, and adjusting policy instruments accordingly.

The transition to a more credible regime also often requires greater exchange rate flexibility. Allowing the exchange rate to fluctuate in response to market conditions improves resilience to external shocks and enables monetary policy to focus on internal stability rather than defending a fixed parity.

Final Comments

Inflation is a complex phenomenon that requires a coordinated response between fiscal and monetary policy. In Bolivia’s case, the current situation is concerning but not irreversible. With an appropriate institutional framework and serious political commitment, it is possible to restore price stability and rebuild confidence in the national currency. However, this process will be neither immediate nor cost-free.

The main obstacle, beyond economic variables, seems to be the disconnect between the urgency of the problem and the response of public institutions. As inflation accelerates and the macroeconomic environment deteriorates, the Central Bank continues to finance the fiscal deficit and focus its efforts on initiatives unrelated to its core mandate. For example, during 2025 it has actively promoted events centered on “digital economy”6, a relevant topic but marginal compared to the loss of control over the general price level.

Meanwhile, the government faces a context marked by electoral tensions and severe fiscal constraints. Instead of implementing a structural adjustment or sustainability plan, it has opted for short-term measures. A glance at the official fanpage of the Ministry of Economy reveals a strategy focused on securing external loans and palliative measures, such as the recent loan payment moratorium proposals, which shift the burden to the financial system without addressing the underlying imbalances.

In this context, it is encouraging that most presidential candidates, at least in their government plans, acknowledge the need to reduce public spending as an essential component to restoring macroeconomic stability. However, one crucial aspect remains unresolved: the “how”. Without a concrete, credible, and technically feasible proposal, the commitment risks being diluted into general statements. The almost five months remaining until the next administration takes office may seem like an eternity unless a realistic and responsible roadmap is developed now.

CEPAL data is available until May 2025 and can be consulted here. The graph will be updated once the May data is released. ↩︎

For an accessible introduction to these theories, see the recent essays by the St. Louis Fed and the Richmond Fed. ↩︎

Several central banks have operationalized this mandate through explicit inflation targets, such as the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve, both aiming for a 2% annual inflation rate. ↩︎

According to the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL), it is not necessary for the deficit to be directly financed by the central bank for inflation to occur. It is enough for the market to perceive that the deficit is unsustainable for inflation expectations to adjust upward, triggering anticipated price increases. ↩︎

See Inflation targeting for an overview of the regime adopted by countries such as Chile, Peru, Colombia, and Brazil. ↩︎

For example, in April 2025 the Monetary Conferences focused on the topic of “Monetary Policy in the Digital Era”, and in June 2025 the 18th BCB Economists Meeting addressed the “Advances and Challenges of the Digital Economy”. ↩︎