Bolivia: A History of Fiscal Incontinence

The Diagnosis: Deficit First, Inflation Later

It can be argued that Bolivia’s economic history is, to a large extent, the history of its fiscal incontinence. Since gaining independence in 1825, the country has failed to establish fiscal discipline that balances its always volatile revenues with its ever-growing expenditures. This failure has led to recurring cycles of fiscal crises resulting in inflation and currency depreciation.

Broadly speaking, Bolivia has followed two fiscal behavior patterns:

- The first involves increased spending to finance what is considered a priority, such as wars or revolutionary movements. This pattern was predominant in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

- The second pattern, more evident in recent decades, is the boom-and-bust cycle of natural resource prices, leading to rising public spending and excessive borrowing.

In both cases, the consequence is the financing of the deficit through the Central Bank. However, it is this second pattern that this post will reflect upon.

This second mechanism can be conceptually described as follows: exogenously, a new technology is discovered in the world or a war needs funding, and a resource produced by Bolivia (such as silver, rubber, tin, gas, and now lithium) is in demand, driving up its price. In response, the state takes control of the resource through public enterprises, generating extraordinary fiscal revenues.

These revenues trigger an aggressive cycle of public spending, often without regard for need, efficiency, or sustainability. But when the resource price falls and extraordinary revenues vanish, the state turns to borrowing to maintain spending levels. This expenditure often becomes a political commitment to beneficiary groups that offer political support.

Initially, borrowing is external, as it does not immediately distort domestic markets. However, this has a limit: when international creditors perceive a rising risk of default, funding is restricted. At this point, the state turns to the Central Bank, which begins financing the fiscal deficit through money issuance—known as “deficit monetization”1. Sound familiar? It is exactly what has happened in Bolivia in recent years.

This process is far from harmless, as it ultimately generates inflation and depreciation. Inflation, in this context, arises because economic agents anticipate future excess currency and accelerate their spending decisions, further pressuring prices. Depreciation occurs because a significant share of household spending shifts to purchasing foreign currency as a value-preserving mechanism. Inflation and depreciation then reinforce each other. This is, among other factors, the result of a latent fiscal problem.

This pattern is neither new nor isolated. As documented by Professor Gustavo Prado in his studies on 19th-century Bolivian economics, even in the early republican years, the state failed to establish a sustainable fiscal system and resorted to issuing debased currency (lower intrinsic value than nominal value) to finance its deficits. This led to chronic inflation and, clearly, currency depreciation. Prado notes:

The decree of October 10, 1829, ordered the Mint of Potosí to reduce the fineness of fractional coins (from half a peso downward) to 8 dineros, or 666.66 per thousand. In other words, the intrinsic value of debased (adulterated) currency compared to strong (unadulterated) currency was only 73.84%. The manifest objective of the decree was to reduce the outflow of silver coins abroad. This sought to alleviate the domestic shortage of small silver coins. The profits from this minting would fund gold mining in the country. […] Minting profits were used to cover urgent current government expenditures, notably military expenses. (Prado, 2001, p. 154).

The same occurred in the 1930s during the Chaco War with Paraguay and in the 1950s when the Paz Estenssoro government had to finance mine nationalization and new social spending. In both cases, the government turned to monetary issuance to finance the fiscal deficit, leading to chronic inflation and currency depreciation (Prado, 2006).

Economic researcher J.A. Peres-Cajías, in his studies of Bolivia’s public finances from 1882 to 2010, details the “structural fragility of fiscal revenues” and chronic dependence on a few export products. For example, he writes:

Using this new quantitative evidence, the paper shows that Bolivian government revenues and expenditures were particularly low and volatile until the late 1980s. It also shows that the importance of social public spending within total public spending has increased since the late 1930s. Regarding the structure of public revenues, the paper highlights that beyond some changes in the relative importance of each category, Bolivia has always had an unbalanced structure: from the late 19th century to the early 1980s, the state depended heavily on trade taxes; later, on indirect domestic taxes and revenues from oil and gas exploitation. (Peres-Cajías, 2014, p. 79, own translation)

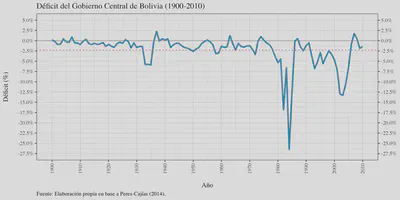

Using reconstructed data from the central government (excluding subnational governments and state-owned enterprises), one observes that fiscal deficits have been a constant in Bolivia’s history. On average, the central government’s deficit is nearly -2.5% of GDP2.

The figure clearly highlights the 1980s. As previously discussed (e.g., in this post), the country faced an external debt crisis that led to hyperinflation, partly triggered by the collapse of tin prices—then Bolivia’s main export3.

More recently, authors like Saavedra-Caballero and Villca (2024) and Kehoe, Machicado & Peres-Cajías (2019) have documented the fragility of Bolivia’s public accounts due to the dependency of fiscal revenues on international commodity prices. Back in 2019, they noted:

Bolivia’s current economic situation shows troubling similarities to the policies of the 1970s. There is a fixed exchange rate, international reserves are falling, and the fiscal deficit is growing. If the government fails to act, this situation could lead to a balance of payments crisis as agents realize that reserves are running out and the Central Bank of Bolivia cannot maintain the de facto fixed exchange rate. (Kehoe, Machicado & Peres-Cajías, 2019, pp. 31-32, own translation)

Two Modest Proposals

Before presenting the proposals, it’s important to clarify that they will not solve the current crisis, but they can help generate credibility and an institutional framework that enables a solution. They should not be seen as rigid but can be adopted gradually. What matters is that they are adopted and institutional mechanisms are created to ensure compliance. In this regard, the proposals are:

1. Fiscal Rules

The first proposal is to establish fiscal rules that limit public spending and compel the government to balance its accounts. These rules could include a cap on the fiscal deficit and a mechanism that adjusts public spending based on fiscal revenues, excluding extraordinary revenues from natural resources.

Several countries have implemented such rules. For instance, Chile’s Fiscal Responsibility Law No. 20128 creates an institutional framework that requires the government to formulate fiscal policy based on a structural balance rule, adjusting revenues and expenditures according to the economic cycle and copper prices. This rule aims to maintain long-term public finance sustainability, limit excessive debt, and promote responsible use of windfall revenues. The law also includes exception mechanisms (escape clauses), transparency through periodic technical reports, and oversight by an Autonomous Fiscal Council.

Paraguay has implemented fiscal rules since 2013 under Law No. 5098 on Fiscal Responsibility, which limits public spending and establishes an institutional framework for fiscal policy formulation. In particular, Article 7 states:

Article 7 – Macrofiscal rules for drafting and approving the General Budget of the Nation. Annual General Budget laws shall follow these rules:

- The annual fiscal deficit of Central Administration, including transfers, shall not exceed 1.5% of estimated GDP for that fiscal year.

- The annual increase in primary current expenditure of the public sector shall not exceed the interannual inflation rate plus 4%. Primary current expenditure is defined as total current spending excluding interest payments.

- Salary increases may only be included when there is an increase in the minimum wage. The increase shall be proportional and incorporated in the following fiscal year’s budget.

While the specific rule must be carefully studied, the goal is clear: prevent the government from persistently spending more than it earns and thus avoid resorting to monetary issuance to finance deficits.

2. Prohibition of Deficit Monetization

In theory, the Central Bank of Bolivia should not monetize the fiscal deficit. I say “should not” not as a personal desire but because Law No. 1670 of the Central Bank of Bolivia states so. In particular, Article 22 provides:

Article 22. The BCB may not grant credit to the public sector nor incur contingent liabilities on its behalf. Exceptionally, it may do so for the National Treasury with a two-thirds vote of the Board members present, in the following cases:

a) To address urgent needs arising from declared public calamities or internal or international unrest.

b) To address temporary liquidity needs, within the limits of the monetary program.

Clearly, this article—intended as an escape clause for exceptional situations—has been repeatedly used to finance the fiscal deficit. The sharp increase in BCB credit to the National Treasury in recent years clearly reflects deficit monetization. As noted in a previous post:

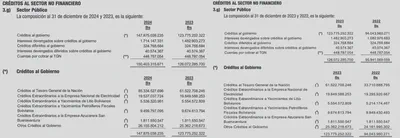

“In 2023, the equivalent of USD 4.39 billion in credits were granted to the public sector (at the official exchange rate), 92.3% of which went to the National Treasury under the concept of Temporary Liquidity Credit to the TGN. Additionally, in 2024, the BCB granted [an equivalent of] USD 3.55 billion in public sector credits, with 97.9% to the TGN under the same concept. Notably, 2023 financing was about 10% of GDP, similar in magnitude to the fiscal deficit, and 2024 is expected to be slightly lower.”

The BCB reports this data in its Annual Financial Statements for both 2022–2023 and 2023–2024.

In this context, I propose modifying Article 22 of the Central Bank Law, eliminating item b), which currently allows financing to the Treasury under the ambiguous notion of “temporary liquidity needs.” This provision, far from serving as a true emergency clause, has been recurrently used to cover persistent fiscal deficits. Its removal would compel the government to turn to alternative financing mechanisms, such as issuing domestic debt via the Bolivian Stock Exchange or seeking external financing under market conditions. In both cases, the state would be subject to market discipline: if agents perceive higher risk of default, financing costs would rise, thus incentivizing fiscal restraint.

As for item a), which allows financing in cases of public calamity or internal/international unrest, I initially propose its removal as well, following the example of countries with stricter prohibitions. Chile, for instance, in its Central Bank Organic Law (Law No. 18.840), states in Article 27 that “No public expenditure or loan shall be financed with direct or indirect credit from the Bank,” with the sole exception of wartime. Peru follows a similar line: Article 84 of its Constitution prohibits Central Bank financing to the Treasury, and Article 77 of its Organic Law reinforces this, only allowing secondary market purchases under strict conditions.

However, item a) could initially be maintained with stricter limits—for example, tying it to a percentage of the Central Bank’s annual profits, and establishing a maximum cap, such as 5% of the BCB’s total assets. This would allow the Central Bank to provide short-term emergency support without resorting to direct monetary issuance, thereby preserving its independence and price stability mandate.

Conclusions

Bolivia’s fiscal trajectory has been marked by persistent deficits, often financed through Central Bank money creation. This pattern has generated inflationary pressures, cycles of instability, and low credibility in macroeconomic management. While the causes are structural and multifaceted, institutional reforms can help mitigate this dynamic.

This post proposes two concrete reforms: (i) implementing fiscal rules that cap the deficit and moderate spending growth, and (ii) explicitly prohibiting monetary financing to the National Treasury. These measures should be seen as complementary, not substitutes.

It must be acknowledged that Central Bank independence is functionally limited if the government runs permanent deficits. In such contexts, pressure to finance spending through quasi-fiscal mechanisms or legal exceptions grows, undermining monetary policy credibility.

Thus, the joint implementation of a credible fiscal rule and the reform of Article 22 of the Central Bank Law constitute a minimum foundation to strengthen fiscal sustainability and preserve monetary stability in the medium term.

References

- Kehoe, T. J., Machicado, C. G., & Peres-Cajías, J. (2019). The monetary and fiscal history of Bolivia, 1960–2017 (NBER Working Paper No. 25523). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w25523

- Morales, J. A., & Sachs, J. D. (1989). Bolivia’s economic crisis. In J. D. Sachs (Ed.), Developing country debt and the world economy (pp. 57–80). University of Chicago Press.

- Peres-Cajías, J. A. (2014). Bolivian Public Finances, 1882–2010. The Challenge to Make Social Spending Sustainable. Revista de Historia Económica / Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, 32(1), 77–117. https://doi:10.1017/S0212610914000019

- Prado, G. A. (2001). Economic Effects of Currency Adulteration in Bolivia, 1830–1870. Revista de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, (1), 35–76. http://www.revistasbolivianas.ciencia.bo/scielo.ph

More broadly, this process is known as the resource curse, which refers to the tendency of resource-rich countries to experience slower economic growth, greater corruption, and less democracy than countries with fewer natural resources. ↩︎

Data available at the author’s website: https://joseperescajias.com/data/ ↩︎

Juan Antonio Morales offers a broader perspective in the book A Century of Economy in Bolivia (1900–2015), edited by Fundación Konrad Adenauer and Plural Editores, and more specifically in Sachs & Morales (1989). ↩︎