Bolivia: Between inflation and the lack of Central Bank independence

Introduction

One of the key conditions for sustained growth in any country is macroeconomic stability. For instance, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) states:

Macroeconomic stability exists when key economic relationships are in balance, such as between domestic demand and output, the balance of payments, fiscal revenue and spending, and savings and investment. However, these relationships don’t need to be exactly balanced. Imbalances—like fiscal or current account deficits or surpluses—are perfectly compatible with economic stability, as long as they are sustainably financed.

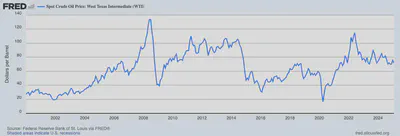

In this sense, Bolivia has enjoyed relative stability in recent years, especially since 2006, when it benefited from a global commodity boom—particularly oil—which increased the value of natural gas exports to Brazil and Argentina by YPFB (the state oil company), since gas prices were indexed to oil prices. This allowed the Central Bank of Bolivia (BCB) to accumulate international reserves and the government to run fiscal surpluses.

However, since at least 2014, natural gas export revenues have fallen, resulting in a drop in BCB reserves, rising external debt, and a persistent fiscal deficit. This trend is also documented in Saavedra-Caballero & Vilca (2024).

What’s the issue? Due to trade and fiscal deficits, rising debt, and the loss of reserves, Bolivia’s core macroeconomic relationships are no longer in balance—and thus, macroeconomic stability seems to be a thing of the past.

In this context, the BCB has taken on a central role in Bolivia’s economy, particularly as of 2024 when inflation surged—reaching 13.22% in February 2025 (year-on-year), a figure that has alarmed the public.

According to Law No. 1670, the BCB’s mandate is:

Article 2: The purpose of the BCB is to preserve the internal purchasing power of the national currency.

Since price stability is its main goal, it’s reasonable that all eyes are now on the BCB. Inflation is a complex phenomenon and particularly difficult to manage in small, open economies like Bolivia’s. Since 2011, when the exchange rate was fixed to the dollar, the BCB’s inflation control strategy has relied on anchoring inflation expectations through exchange rate stability and controlling domestic credit growth (to the public and private sectors), which implies that money supply should not grow faster than output1.

Moreover, if businesses and households expect prices to rise, they will change their behavior accordingly—consuming today rather than tomorrow, and setting prices preemptively. This happens when inflation expectations become unanchored—i.e., when agents no longer believe the BCB can control inflation. This has already happened, as evidenced by the parallel dollar market where the exchange rate far exceeds the official one. The BCB has thus lost its “nominal anchor”—and with it, public confidence in its capacity to manage inflation.

In this situation, as prominent figures like Juan Antonio Morales have suggested, the BCB should have begun tightening monetary policy, reducing the money supply. But such tightening comes at a cost—credit contracts, investment and consumption fall, and unemployment rises. Politically, such outcomes are to be avoided at all costs.

Thus, for the BCB to take such actions, it must be independent—at least from the political cycle. However, the BCB has aligned itself with political interests, increasing the money supply by financing the government’s fiscal deficit, which has only accelerated inflation and eroded trust in the national currency.

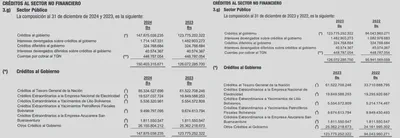

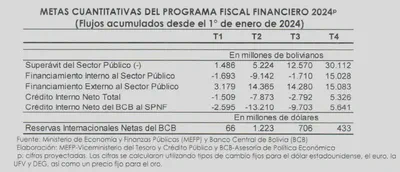

Let’s look at some data from the BCB’s audited financial statements, both for 2022–2023 and 2023–2024:

For example, in 2023, the BCB granted public sector loans worth USD 4.392 billion (at the official exchange rate), of which 92.3% went to the National Treasury (TGN) under the heading of Temporary Liquidity Credit to the TGN. In 2024, it granted another USD 3.547 billion, 97.9% of which went to the TGN. The 2023 financing was roughly 10% of GDP—similar in size to the fiscal deficit—and 2024’s looks only slightly smaller.

This monetary financing not only fuels inflation expectations but also exposes the BCB’s lack of autonomy. Law No. 1670 states that the BCB may not finance the public sector, except under exceptional circumstances:

Article 22: The BCB may not grant credit to the public sector or assume contingent liabilities on its behalf. Exceptionally, it may do so for the National Treasury, with two-thirds approval of the BCB Board present, in the following cases: a) To address urgent needs stemming from public disasters or internal/international unrest, declared by Supreme Decree; b) To address temporary liquidity needs, within the limits of the monetary program.

Clause (b) allows credit to the Treasury only if temporary and within the monetary program’s limits. Yet the BCB and the Ministry of Economy (MEFP) have repeatedly modified the monetary program to increase deficit financing. For example, the 2024 Fiscal-Financial Program (PFF) capped BCB financing at USD 2.191 billion, yet it ultimately disbursed USD 3.547 billion—62.1% more than authorized. If the MEFP and BCB can rewrite the rules at will, what’s the point of setting financing limits? Essentially, none.

Moreover, such loans require two-thirds approval from BCB Board members present. According to Law No. 1670:

Article 45: The Board shall consist of the BCB President and five Directors. The President shall be appointed by the President of the Republic from a shortlist approved by two-thirds of the Chamber of Deputies. The term is six years, non-renewable until an equivalent period has passed. Directors shall also be appointed from similar shortlists and serve five-year non-renewable terms.

In practice, however, the BCB’s current Board bypasses legislative approval. Most members are interim (“a.i.”) appointees, nearly all with ties to past MAS administrations. The most emblematic case is the current BCB President, Edwin Rojas, who was sworn in by the Minister of Economy. This raises serious doubts about the BCB’s autonomy—suggesting it is an extension of the MEFP. Economist Hugo Rodríguez, a former BCB official, expresses similar concerns in this article.

In today’s delicate situation, Bolivia needs a Central Bank with enough independence to preserve macro stability and take the tough decisions politicians won’t. That is the purpose of modern central banks. And this is not an unfamiliar scenario—Bolivia has already endured one of the worst postwar hyperinflationary episodes in history under similar conditions.

Of course, the BCB alone cannot solve the crisis—it depends on restoring fiscal sustainability, attracting foreign investment, and making the economy more flexible. But at the very least, it must not worsen the crisis by continuing to finance the fiscal deficit, which only fuels inflation. Therefore, it is imperative that the BCB regains its autonomy. In the future, stronger safeguards must be in place to ensure central bank independence—especially during crises. If this is not feasible, dollarization and handing over monetary policy to a foreign central bank—like Ecuador did—may need to be considered.

If money supply grows faster than production over time, prices will rise, i.e., inflation will occur. So, the BCB should control the money supply to prevent price hikes. However, the relationship between monetary aggregates and inflation is complex and not strictly linear. I elaborate further in this tweet. ↩︎