Bolivia’s Hyperinflation and Stabilization: Nearly 40 Years Since D.S. 21060

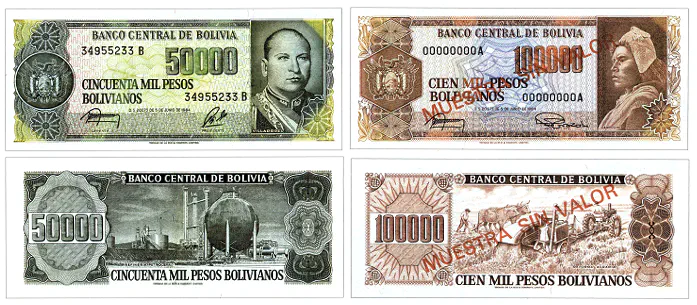

In the 1980s, Bolivia experienced one of the most critical periods in its history: one of the highest hyperinflations in modern history—without being driven by war. In 1985, monthly inflation reached nearly 60%, equivalent to an annual rate of approximately 26,000%1.

As documented by Sachs (1986), inflation became a problem as early as 1978:

This inflationary process continued until May 1982, when Bolivia entered the hyperinflationary phase. According to the “classic” definition, hyperinflation occurs when prices increase by 50% or more in a single month. Once this point was reached, it wasn’t halted until August 1985, with the stabilization plan introduced by President Paz Estenssoro. In other words, inflation persisted for about four years, with hyperinflation lasting an additional three.

Two documents describe Bolivia’s hyperinflation and subsequent stabilization in detail. The first is The Bolivian Hyperinflation and Stabilization by Jeffrey D. Sachs (1986), and the second is Bolivia’s Economic Crisis (1987) by Sachs and Juan Antonio Morales Anaya2. Both texts explain the institutional context and proximate and structural causes of the crisis.

The overall process can be summarized as follows: a government experiences a temporary commodity boom and borrows internationally to increase spending and public investment in politically aligned sectors. When the boom ends and external credit dries up, political unwillingness to adjust fiscal accounts leads to domestic financing, triggering price increases (basic goods and exchange rate). In a weak institutional context, this becomes a vicious cycle, and the government increasingly relies on domestic credit, eventually leading to hyperinflation.

While today’s context, circumstances, and actors differ from the 1980s, the structure of Bolivia’s economy and society has remained relatively unchanged. A dispassionate analysis of one of the country’s worst crises may help us learn from the past and avoid repeating it.

The remainder of this article, based on the above documents, describes the hyperinflationary process of the 1980s, highlighting elements that resemble Bolivia’s current situation.

1 The Political and Institutional Problem

According to Sachs (1986), the root cause of Bolivia’s hyperinflation was institutional weakness:

“Rather, at a fundamental level, hyperinflation arose from deep weakness in Bolivia’s political institutions, which made it impossible for many successive governments to stop the processes of rising deficits and falling tax collections.”

This institutional problem dates back at least to the 1952 revolution and is reflected in the country’s chronic ungovernability. A brief look at recent political history reveals this pattern:

As Morales and Sachs (1987) point out:

Since the 1952 Revolution, all social factions have looked to the central government to satisfy their distributive demands. The battle for political power has also been a battle for a larger share of national income. This distributive struggle has been particularly harmful, as it has occurred alongside a secular decline in mining sector surpluses.

In essence, Bolivia’s economy, from 1952 to 1985, lacked clear rules and effective checks and balances. The absence of such mechanisms led to a system where various interest groups used the state to impose their agendas and redistribute wealth—often by force. Morales and Sachs (1987) summarize this as follows:

A fourth effect has been the degeneration of politics into fierce battles between those “in government” and those “outside of it.” With the state viewed as a redistribution tool, successive governments come to see public funds as available for personal gain or political clientelism.

1.1 Parallels with the Present

Institutional fragility from the 1980s remains largely unresolved. While Bolivia is no longer ruled by military regimes, institutional weakness is still evident—for example, in the inability to reach agreements in the legislature (see here, here, and here), or in the fact that social demands—regardless of legitimacy—are expressed through marches and blockades, which disrupt everyday life.

These actions are typically organized by interest groups (see miners, street vendors, medical workers, freight transporters), and do not necessarily improve overall welfare when met.

Why is this a problem? A fragmented society with high levels of conflict increases the cost of reaching agreements. For instance, suppose the government plans a tax reform to close the fiscal deficit by expanding the tax base and reducing spending by cutting fuel subsidies or shuttering loss-making state enterprises. While necessary for macroeconomic stability, such measures would provoke protests from affected groups, rendering reforms politically unviable.

This scenario unfolded under President Siles Zuazo. As Morales and Sachs (1987) recall:

It should be noted that Siles Zuazo attempted several stabilization programs (November 1982, November 1983, April 1984, August 1984, November 1984, and February 1985), but each attempt was thwarted by political opposition in Congress and even the government’s apparent “allies” in the labor movement.

In other words, even during a clear economic disaster and despite political will, reforms were blocked by factionalism and special interests.

From this perspective, I remain pessimistic about Bolivia’s current prospects. Avoiding another crisis requires:

- A shared diagnosis of structural economic problems (fiscal deficit, low productive capacity, rigid labor market and informality, weak rule of law).

- A coherent reform agenda, ideally supported—or at least accepted—by political and social organizations to ensure viability.

- Implementation of reforms alongside temporary compensation for vulnerable groups. These compensations should be targeted and time-bound, given that reforms may initially lead to reduced investment, lower consumption, or price increases.

Such a strategy requires political maturity and the ability to endure short-term losses for medium- and long-term gains—conditions that, in my opinion, are unlikely to materialize.

2 The Economic Problem

In Sachs’ account, the immediate cause of Bolivia’s hyperinflation is described as follows:

“The proximate cause of the hyperinflation is the loss of international creditworthiness of the government in the early 1980s. Between 1975 and 1981, several Bolivian governments relied heavily on foreign debt to finance public spending. The combination of large external debt, domestic political instability, poor macroeconomic management, a weak tax system, and deteriorating export prospects prevented the Bolivian government from obtaining new international loans after 1981. When foreign capital inflows ceased in early 1982, the government did not raise taxes or reduce spending, but instead replaced foreign capital with domestic credit expansion as the source of funding. The rapid expansion of the money supply then triggered the inflationary process.”

Broadly speaking, the hyperinflation story can be summarized as follows:

The state manages a commodity boom through state-owned enterprises, gaining revenue from profits and taxes, while accumulating foreign reserves through the Central Bank.

The government allocates this revenue to politically aligned sectors, generating a level of public spending that becomes hard to reduce. It also takes on foreign debt to finance further spending.

As the fiscal deficit becomes unsustainable and external credit dries up, the government turns to domestic borrowing—mainly from the Central Bank. Under a fixed exchange rate regime, falling reserves erode confidence in the currency and trigger black markets.

Financing the deficit with domestic credit fuels inflation, widening the gap between official and parallel exchange rates. Inflation reduces real tax revenue (via evasion and contraband) and curtails imports, worsening the fiscal imbalance. Exporters, under a fixed official rate, may also divert foreign currency through unofficial channels.

The government is unable to generate a fiscal surplus due to a narrow tax base and political inability to cut spending. Continued reliance on domestic credit further fuels inflation and erodes monetary credibility.

Stabilization demands painful adjustments: closing the fiscal deficit, unifying exchange markets, and diversifying exports. These reforms are politically costly and offer no short-term guarantees of success.

2.1 Some Data

To provide a sense of scale, below are key indicators from the inflationary and hyperinflationary years.

First, external debt as a share of GDP increased rapidly in the years leading up to hyperinflation:

This situation, along with Bolivia’s extreme dependence on gas and mineral exports to earn foreign currency, set the stage for the crisis:

As Sachs and Morales noted, the fall in tin prices during the early 1980s caused Bolivia’s economy to collapse. International lenders pulled out, and the government resorted to monetizing its fiscal deficit.

Tax revenues also collapsed between 1982 and 1985, forcing the government to rely even more heavily on Central Bank financing:

2.2 Adjustment Measures

To conclude this section, here’s the Spanish translation of Table 6 from Sachs (1986), summarizing the adjustment measures taken to stop hyperinflation and their implementation status as of mid-1986:

| Policy Area | Key Initiatives | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange Rate | Unification of current and capital account rates; full convertibility | Fully implemented (Sep 1985) |

| Public Sector Prices | Increased to world levels (especially energy and food) | Fully implemented (Sep 1985) |

| Consolidated Public Budget | Target deficit of 6.3% of GDP (5.3% to be financed externally) | Approved by Congress (May 1986) |

| Import Regulations | Flat 20% tariff, elimination of quotas and non-tariff barriers | Quotas eliminated immediately; Tariff reform (Aug 1986) |

| Private Sector Wages & Employment | Deregulated wages and hiring/firing (except minimum wage) | Fully implemented (Sep 1985) |

| Private Sector Prices | Removal of all price controls (except public transport & utilities) | Fully implemented (Sep 1985) |

| Public Sector Wages & Employment | Wage freezes in 1985–86 periods; employment cuts in state firms | Freezes in effect; layoffs not yet implemented |

| State-Owned Enterprises | Decentralization of major SOEs | Most actions still pending |

| Taxation | Increased payments from YPFB; major tax reform incl. VAT & income taxes | Passed by Congress (May 1986) |

| International Financial Institutions | IMF Standby Agreement; restored creditworthiness with WB and IDB | Approved (June 1986); Up to date on obligations |

| Foreign Creditors | Paris Club debt rescheduling; negotiations with commercial banks | Paris terms agreed (June 1986); bank talks ongoing |

| Interest Rates | Liberalized commercial bank interest rates | Fully implemented (Sep 1985) |

These policies, adopted under President Paz Estenssoro’s Supreme Decree 21060, marked a radical shift in Bolivia’s economic policy. Although the long-term social and economic impact remains a matter of debate, in the short term they successfully curbed hyperinflation and stabilized the economy. Notably, the reforms were broad-based—spanning exchange rate, labor, fiscal, and trade policy.

3 Final Remarks

This article has aimed to summarize Bolivia’s hyperinflation during the 1980s and to highlight certain parallels with today’s economic situation. While this reading is not intended to be exhaustive, it does seek to provoke debate and reflection on the current challenges facing the country. Above all, it serves as a reminder of how costly policy missteps and institutional weaknesses can become.

The Bolivian experience demonstrates that:

- Relying on a temporary commodity boom to finance persistent public deficits is unsustainable.

- When external financing disappears and domestic institutions are weak, monetizing the deficit leads to inflationary spirals.

- Without political consensus or institutional capacity, even well-intentioned reforms may fail.

- Stabilization, though painful, is necessary—and delay only raises the ultimate cost.

While the historical and current contexts differ, Bolivia still faces structural challenges: fiscal imbalances, weak institutions, fragmented political will, and limited external financing options. These circumstances make it crucial to learn from past experiences, especially as inflationary pressures and currency depreciation re-emerge.

If today’s policymakers, economists, and civil society leaders can take one lesson from the crisis of the 1980s, it should be this: rebuilding macroeconomic stability demands not just technical solutions, but also deep political commitment and institutional credibility. Without these, no reform package—no matter how technically sound—can succeed.

This means that if inflation had been exactly 60% each month, and the price of 1 kg of chicken was Bs. 10 on January 1, 1985, it would have risen to Bs. 16 in February, Bs. 25.6 in March, Bs. 40.96 in April, and so on until reaching Bs. 2,814.7 by December 1985. ↩︎